Happy Birthday to the Big Boss!

We just celebrated the 50th anniversary of the movie that changed everything. On October 23, 1971 Bruce Lee’s The Big Boss premiered in Hong Kong to a packed house, and almost fell on its face.

Disappointed by the way Sir Run Run Shaw held Shaw Studios in his iron grip, the production chief, Raymond Chow, and another employee, Leonard Ho, decided to strike out on their own with very little money but big ambitions. Their Golden Harvest studio set itself up as a rival to the massive motion picture powerhouse, but things didn’t get off to a great start. A few journeyman directors like Huang Feng and Lo Wei had made the jump from Shaw to Golden Harvest, and scoring Chung Chang-Hwa, director of the international hit Five Fingers of Death, was a coup, but Golden Harvest still didn’t have what mattered: a star. Shaw owned all of those. Then Lo Wei’s son watched Enjoy Yourself Tonight, a local Hong Kong variety show and saw Bruce Lee strut his stuff. He made his dad watch, and his dad made Raymond Chow watch, and Raymond Chow sent Lo Wei’s wife to LA to negotiate a deal. When she arrived, Bruce had just discovered that he couldn’t make his mortgage payment, so she maneuvered him into signing a two-film contract.

20 days later, on July 18, 1971, Bruce arrived in Pak Chong, Thailand, 100 miles north of Bangkok, to film a janky low budget production called The Big Boss. The script was a three-page outline. The director was a former Shaw Brothers veteran, the fight choreographer was a former Cathay Studios journeyman, and the star was a former Shaw Brothers contract actor. Everyone hated Bruce. He hated them right back. He had to fight to shoot the action his way. He had to fight to get enough protein in his diet. Things looked grim until Chow fired the director and replaced him with Lo Wei who brought the movie in on time, and a midnight preview was set for Halloween weekend.

Bruce sat in the front of the theater with Linda and Bob Baker, a student from LA he’d invited to work on his next, and probably final movie, for Golden Harvest. Onscreen, Bruce awkwardly delivered his lines as a country bumpkin come to Thailand looking for work. When the first fight erupts, co-star James Tien tells him “Stay out of this,” and he does. Same with the next fight. And the next. Bruce Lee, the world’s most famous fighter, pretty much doesn’t lift a finger for the first hour and twenty minutes of the movie. Instead, the sneering, murderous, drug-smuggling factory boss makes him look like a jerk, lying to him, getting him drunk, turning his friends against him.

It was all part of the plan.

Leonard Ho, Golden Harvest’s silent co-founder, believed that logic and realism didn’t matter in a movie. What mattered was connecting to the audience on an emotional level. For The Big Boss, one colleague remembers, “He insisted that Bruce Lee’s character should suppress his anger and rein in his emotions until the final, cathartic showdown at the end of the film.”

Lee hoped his impotence and simmering rage connected with the premiere audience, but he wasn’t sure.

“As the movie progressed,” Bruce said. “We kept looking at the fans. They hardly made any noise.”

Then, around minute 77, Bruce unleashed the beast. The final fight lasted for 18 minutes. It ended when pretty much everyone in the cast was dead.

“There was about 10 seconds of silence,” Mel Tobias, an audience member said. “They didn’t know what hit them…and then they started roaring.”

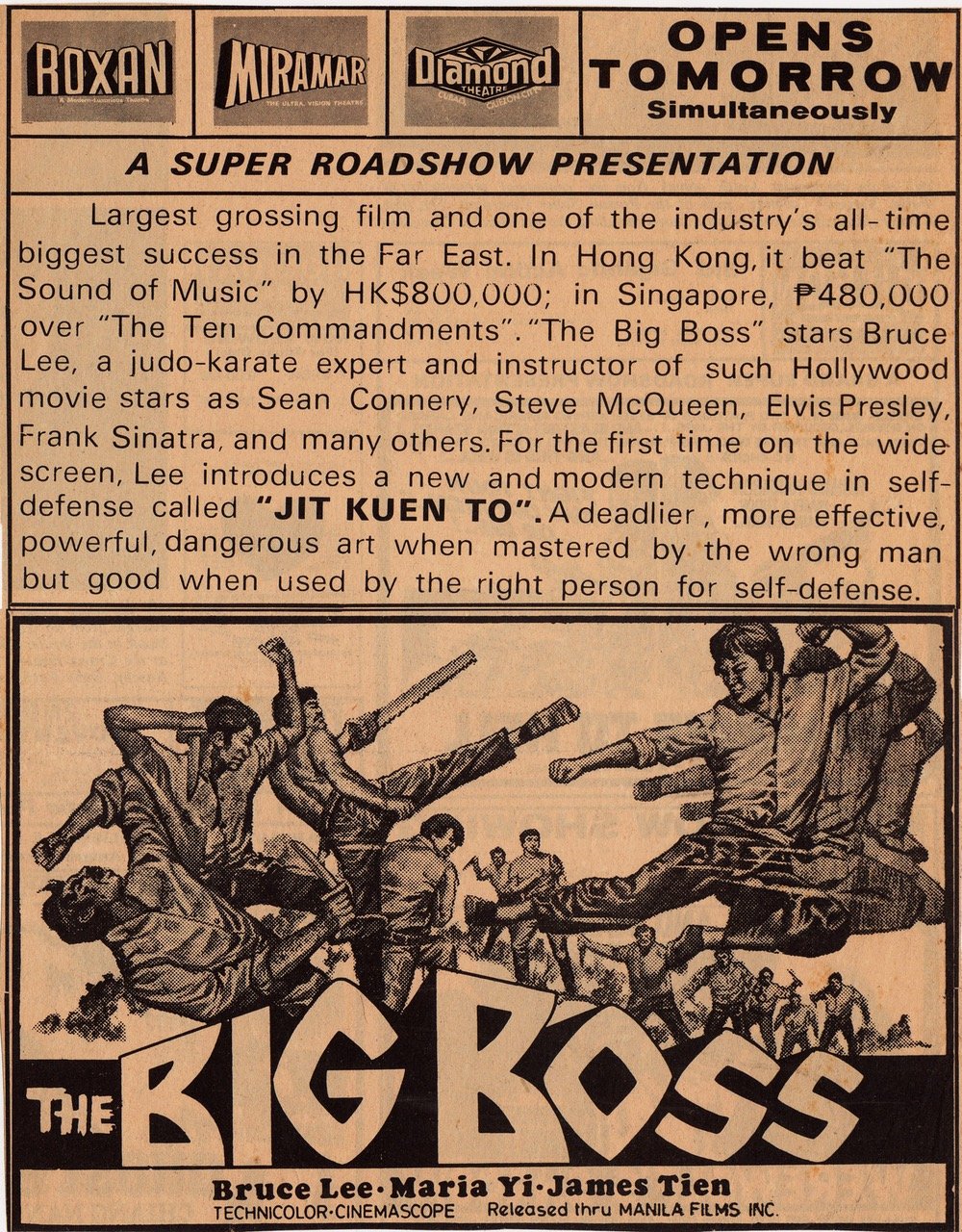

The Big Boss became the highest-grossing movie in Hong Kong history, beating former champion, The Sound of Music. A star was born.

As that star rose, Warner Bros kept calling, trying to get Bruce to sign a contract with them as he made more movies with Golden Harvest: Fist of Fury and Way of the Dragon. Bruce kept playing coy. He’d been burned by Hollywood before and when he went back he wanted it to be on his terms. He wanted to write, direct, and star in his own movies, but he didn’t think he’d made a movie in Hong Kong that looked technically polished enough to wow them in Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, Raymond Chow sent Warner’s Fred Weintraub a print of The Big Boss, hoping to make a sale, but Weintraub never even called him back. Annoyed, Chow eventually sold it to a Chinatown distributor, but what he didn’t know was that Weintraub had used that print to convince his boss, Ted Ashley, to lure Bruce away from Golden Harvest. Without Chow knowing, they began to woo Bruce Lee.

Meanwhile, in 1972, subtitled prints of The Big Boss and Fist of Fury started playing American Chinatowns. Pagoda Films, the distribution arm of the Pagoda Theater in New York City’s Chinatown realized they didn’t need to buy ads, they just had to hold a free press screening and they’d get reviews in all the English-language papers. Those reviews sent some brave Western viewers trooping down to Chinatown to catch the film, introducing them to the real Bruce Lee.

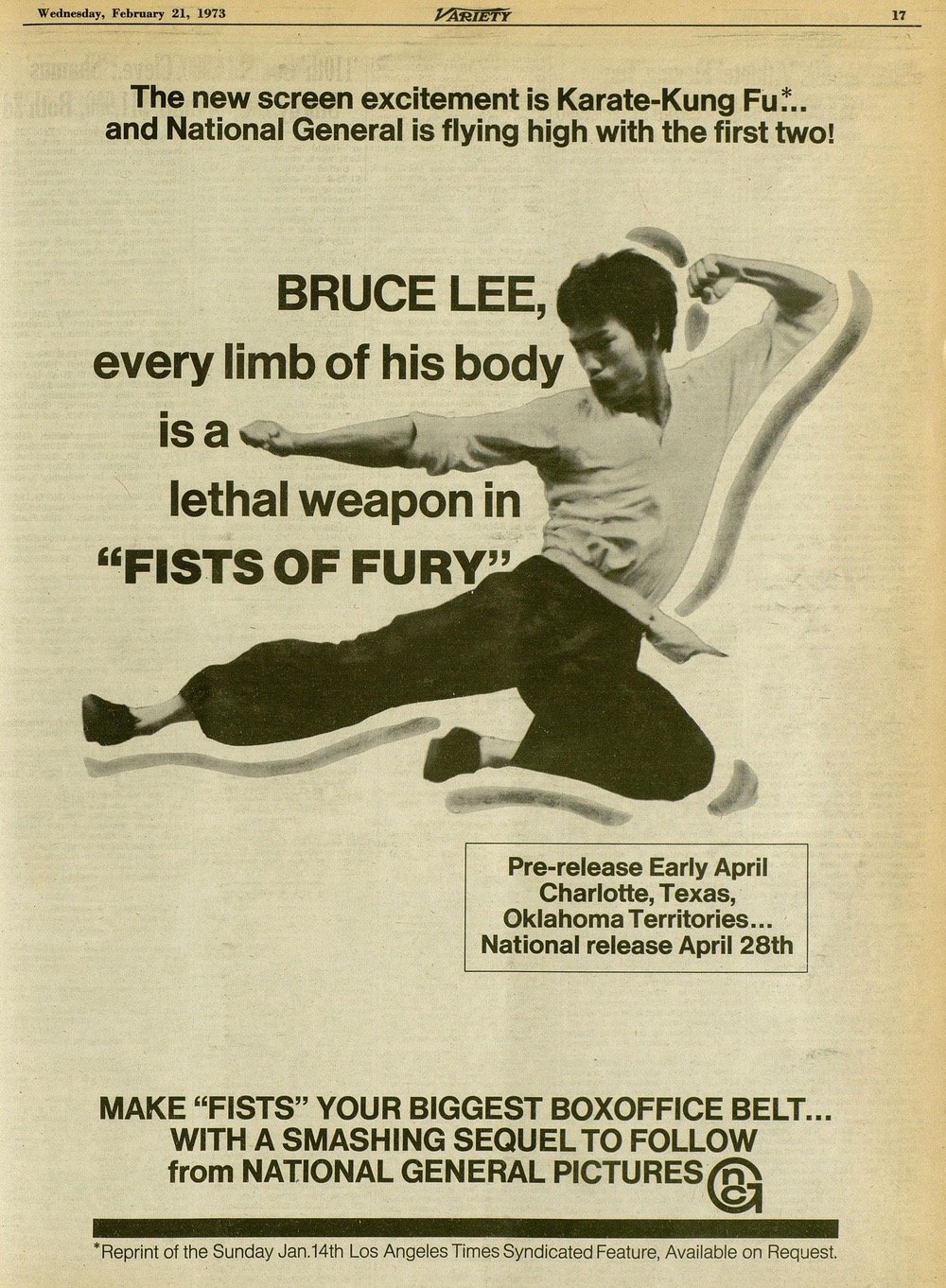

But Raymond Chow knew the movies could find a bigger audience so he re-sold the theatrical rights to Boss and Fist again, this time to a dying distributor named National General. Chow credited Charles Boasberg, its head, as the first Westerner to smell money in Bruce Lee’s films, probably because Boasberg desperately needed movies. National General had been acquired by the American Financial Corporation, an enormous, faceless juggernaut that had already started chopping it up for parts. National’s films mostly came through a deal with First Artists, a vanity studio founded by Barbara Streisand, Steve McQueen, Sidney Poitier, and Dustin Hoffman to release their own pictures. The problem was that these megastars made movies too slowly for a distributor to survive on, so National General looked for off-the-grid pick-ups to fill in the gaps. That’s where Bruce Lee came in.

National General grabbed The Big Boss and Fist of Fury at low prices, dubbed them into English, and changed their titles. The Big Boss became the plural Fists of Fury and Fist of Fury became The Chinese Connection because there had already been a French Connection the previous year so why not? They advertised them as the latest in “karate kung fu movies” because Western audiences had no idea what kung fu was, but they’d heard of karate.

When Bruce found out Chow had sold what he felt were his worst foot forward to an American distributor, he felt betrayed and told Chow he was going to sign with Warners to make a movie called Blood & Steel, based on an old Western script by Weintraub called Kelsey. At risk of losing his first big star, Chow had no choice but to get on board, so Blood & Steel became a Warner Bros/Golden Harvest co-production, and in January, ’73, it started shooting in Hong Kong.

“From the first, nothing went right,” says Weintraub.

(This excerpt is taken from These Fists Break Bricks)